Cloud Atlas (novel)

This article consists almost entirely of a plot summary. (May 2023) |

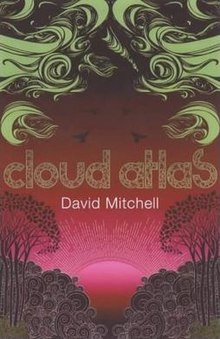

First edition book cover | |

| Author | David Mitchell |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | E. S. Allen |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fantasy, drama |

| Published | 2004 (Sceptre) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 544 (first edition, hardback) |

| ISBN | 0-340-82277-5 (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 53821716 |

| 823/.92 22 | |

| LC Class | PR6063.I785 C58 2004b |

Cloud Atlas, published in 2004, is the third novel by British author David Mitchell. The book combines metafiction, historical fiction, contemporary fiction and science fiction, with interconnected nested stories that take the reader from the remote South Pacific in the 19th century to the island of Hawaii in a distant post-apocalyptic future. Its title references a piece of music by Toshi Ichiyanagi.

It received awards from both the general literary community and the speculative fiction community, including the British Book Awards Literary Fiction award and the Richard & Judy Book of the Year award, it was also short-listed for the Booker Prize, Nebula Award for Best Novel, and Arthur C. Clarke Award. A film adaptation directed by the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer, and featuring an ensemble cast, was released in 2012.

Plot summary

[edit]This section's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (May 2023) |

The book consists of six nested stories; each is read or observed by the protagonist of the next, progressing in time through the central sixth story. The first five stories are each interrupted at a pivotal moment. After the sixth story, the others are resolved in reverse chronological order.

The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing

[edit]In the Chatham Islands during the mid-nineteenth century, Adam Ewing, an American lawyer from San Francisco, keeps a journal as he awaits repairs to his ship. He witnesses a Maori overseer flogging Autua, a Moriori slave. As the ship gets underway, Dr. Henry Goose, Ewing's only friend aboard the ship, diagnoses Ewing's chronic ailment with a fatal parasite and recommends a course of treatment. Meanwhile, Autua has stowed away in Ewing's cabin. When Ewing discloses this to the Captain, Autua proves himself a first-class seaman, and the Captain puts Autua to work for his passage to Hawaii.

Letters from Zedelghem

[edit]In 1931 Zedelghem, near Bruges, Robert Frobisher a recently disowned and penniless young English musician, writes letters to his lover Rufus Sixsmith. Frobisher becomes an amanuensis to elderly composer Vyvyan Ayrs. Frobisher produces Der Todtenvogel ("The Death Bird") from Ayrs's basic melody, which critics laud. Newly emboldened, Frobisher composes his own music. Frobisher and Ayrs' wife Jocasta begin an affair, but her daughter Eva remains suspicious of him. Frobisher sells rare books from Ayrs' collection to a fence, finds the first half of The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing, and asks Sixsmith if he can obtain the second half so Frobisher can finish it. As the summer comes to an end, Jocasta thanks Frobisher for "giving Vyvyan his music back", and Frobisher agrees to stay until the next summer.

Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery (Part 1)

[edit]In the fictional Buenas Yerbas, California, in 1975, Luisa Rey, a young journalist, meets the elderly Rufus Sixsmith in a stalled elevator, and she tells him about her late father, a policeman and later famous war correspondent. After Sixsmith tells Luisa that the Seaboard HYDRA nuclear power plant is not safe, assassin Bill Smoke later kills him in an apparent suicide. Luisa believes the businessmen in charge of the plant are assassinating potential whistleblowers. From Sixsmith's hotel room, Luisa acquires some of Frobisher's letters. Isaac Sachs, a plant employee, gives her a copy of Sixsmith's report. Before Luisa can report her findings on the nuclear power plant, Smoke forces her car—with Sixsmith's incriminating report—off a bridge.

The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish

[edit]In the early twenty-first century London, Timothy Cavendish, a 65-year-old vanity press publisher, experiences high sales after his client murders a book critic. His client's brothers threaten Cavendish for money. Cavendish's wealthy brother Denholme books him into an abusive nursing home. Timothy cannot leave, having signed custody papers and thinking they were a hotel registry. When he tries to flee, a security guard stops and punishes him publicly. He briefly mentions reading a manuscript titled Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery. Settling into his new surroundings and plotting a way out, he has a stroke.

An Orison of Sonmi-451 (Part 1)

[edit]Set in Nea So Copros, a dystopian state in twenty-second-century Korea, derived from corporate culture. The Archivist, a Unanimity worker, records Sonmi-451's story into an "orison", a silver egg-shaped device for recording and holographic videoconferencing. Sonmi-451 is a fabricant waitress at a fast-food restaurant called Papa Song's. Clones grown in vats are the predominant source of cheap labor. The "pureblood" (natural-born) society hinders the fabricants' consciousness by chemical manipulation using a food called "Soap". After twelve years as slaves, fabricants are promised retirement to a fabricant community in Honolulu.

Eventually, Professor Mephi and his student Hae-Joo Im remove her from the restaurant to study and assist her to become self-aware, attending university and expanding her knowledge. She describes watching The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish, when a student interrupts to inform them that Professor Mephi has been arrested. Policy enforcers have orders to interrogate Hae-Joo and kill Sonmi on sight.

Sloosha's Crossin' an' Evrythin' After

[edit]On Big Island after a great societal collapse, the peaceful farmers known as Valley Folk worship a goddess called Sonmi. Zachry Bailey blames himself when the cannibalistic Kona tribe killed his father and enslaved his brother. Occasionally, a technologically sophisticated group known as the Prescients visit and study Big Island. Zachry is suspicious of one Prescient named Meronym, who requests a guide to the top of Mauna Kea volcano. After Meronym cures Zachry's sister from poisoning Zachry reluctantly agrees. They climb to the ruins of the Mauna Kea Observatories, where Meronym explains the orison Zachry found in her room and reveals Sonmi's history. Upon their return, they go with most of the Valley Folk to trade at Honokaa, but the Kona ambush Zachry's people. Zachry and Meronym eventually escape, and she takes him to a safer island. The story ends with Zachry's child recalling that his father told many unbelievable tales, but that this one may be true because he has inherited Sonmi's orison.

An Orison of Sonmi-451 (Part 2)

[edit]Hae-Joo Im reveals that he and Mephi are members of an anti-government rebel movement called Union. Hae-Joo then guides Sonmi in disguise to a ship and shows Sonmi how Nea So Corpos butchers retired fabricants and recycles them into Soap. Any leftovers are used in food for purebloods. Union plans to raise all fabricants to self-awareness and thus disrupt the workforce that keeps the corporate government in power. They want Sonmi to write a series of abolitionist Declarations calling for rebellion. Sonmi is arrested in an elaborately filmed government raid.

Sonmi tells the Archivist that the government instigated everything that happened to her to encourage the fear and hatred of fabricants by purebloods. Sonmi's last wish is to finish watching Cavendish's story.

The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish (Part 2)

[edit]Having mostly recovered from his mild stroke, Cavendish meets a small group of residents also anxious to escape the nursing home: Ernie, Veronica, and the extremely senile Mr. Meeks. Cavendish assists in their plan to steal a car from another patient's son. They seize the car and escape, stopping at a pub to celebrate their freedom. The staff nearly recaptures them, but Mr. Meeks, in an unprecedented moment of lucidity, exhorts the local drinkers to come to their aid, where a brawl breaks out. Cavendish reveals that his secretary blackmailed the gangsters with evidence of their attack. Cavendish returns home and reads the second half of Luisa Rey's story and intends to publish it.

Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery (Part 2)

[edit]Luisa escapes from her sinking car but loses the report, while a plane carrying Sachs blows up. When a Seaboard subsidiary buys her newspaper, Luisa is fired. Bill Smoke booby-traps a copy of Sixsmith's report at a bank, and Joe Napier, a security man and friend of Luisa's father, rescues her. Luise finds a copy of the report aboard the Starfish, Sixsmith's yacht. After a short chase, Smoke and Napier kill each other in a gunfight. Rey exposes the corrupt corporate leaders to the public. She receives from Sixsmith's niece the remaining eight letters from Robert Frobisher to Rufus Sixsmith.

Letters from Zedelghem (Part 2)

[edit]Frobisher continues to pursue his work with Ayrs while developing his Cloud Atlas Sextet. He falls in love with Eva after she confesses a crush on him, despite his affair with her mother. Jocasta suspects this and threatens to destroy his life if he so much as looks at her daughter. Ayrs, bolder with his plagiarism of Frobisher, now demands Frobisher compose full passages and intends to take credit for it. Ayrs threatens to blacklist him by claiming he raped Jocasta if he refuses. In despair, Frobisher works in a nearby hotel to finish his Sextet and hopes to reunite with Eva, convinced that her parents are keeping them apart. He confronts her and discovers her Swiss fiancé. Mentally and physically ill, Frobisher finishes his Cloud Atlas Sextet and decides to kill himself. Before committing suicide, he writes one last letter to Sixsmith and includes his sextet and The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing.

The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing (Part 2)

[edit]The ship makes port at Raiatea, where he observes missionaries oppressing the indigenous peoples. On the ship, Ewing falls further ill and realizes that Dr. Goose is poisoning him to steal his possessions. Autua kills Dr. Goose to save Ewing, who resolves to join the abolitionist movement.

Background and writing

[edit]In an interview with The Paris Review, Mitchell said that the book's title was inspired by the music of the same name by Japanese composer Toshi Ichiyanagi: "I bought the CD just because of that track's beautiful title." Mitchell's previous novel, number9dream, was inspired by music by John Lennon. Both Ichiyanagi and Lennon were husbands of Yoko Ono, and Mitchell has said this fact "pleases me ... though I couldn't duplicate the pattern indefinitely."[1] He has stated that the title and the book address reincarnation and the universality of human nature, with the title referring to both changing elements (a "cloud") and constants (the "atlas").[2]

Mitchell said that Vyvyan Ayrs and Robert Frobisher were inspired by English composer Frederick Delius and his amanuensis Eric Fenby.[3] He has also noted the influence of Russell Hoban's novel Riddley Walker on the Sloosha's Crossin' story.[4]

Reception

[edit]Cloud Atlas received positive reviews from most critics, who felt that it managed to successfully interweave its six stories.[5] On Metacritic, the book received a 82 out of 100 based on 24 critic reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[6] The Daily Telegraph reported on reviews from several publications with a rating scale for the novel out of "Love It", "Pretty Good", "Ok", and "Rubbish": Times, Independent, Observer, Independent On Sunday, Spectator, and TLS reviews under "Love It" and Daily Telegraph and Sunday Times reviews under "Pretty Good" and Literary Review review under "Ok".[7] According to Book Marks, based on American press, the book received "positive" reviews based on eleven critic reviews with six being "rave" and one being "positive" and four being "mixed".[8] The BookScore gave it a aggregated critic score of 9.0 based on an accumulation of British and American press reviews.[9] In November/December 2004 issue of Bookmarks, the book received a ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (4.00 out of 5) based on critic reviews with a summary saying, "Critics on both sides of the Atlantic rave over Cloud Atlas, British novelist Mitchell’s third novel".[10] Globally, the work was received generally well with Complete Review saying on the review consensus, "Not quite a consensus, but most very impressed".[11]

(4.00 out of 5) based on critic reviews with a summary saying, "Critics on both sides of the Atlantic rave over Cloud Atlas, British novelist Mitchell’s third novel".[10] Globally, the work was received generally well with Complete Review saying on the review consensus, "Not quite a consensus, but most very impressed".[11]

The BBC's Keily Oakes said that although the book's structure could be challenging, "David Mitchell has taken six wildly different stories ... and melded them into one fantastic and complex work."[12] Kirkus Reviews called it "sheer storytelling brilliance."[13] Laura Miller of The New York Times compared it to the "perfect crossword puzzle," in that it was challenging to read but still fun.[14] The Observer's Hephzibah Anderson called it "exhilarating" and commented positively on the links between the stories.[15] In a review for The Guardian, Booker Prize winner A. S. Byatt wrote that it gave "a complete narrative pleasure that is rare."[16] The Washington Post's Jeff Turrentine called it "a highly satisfying, and unusually thoughtful, addition to the expanding 'puzzle book' genre."[17] In its "Books Briefly Noted" section, The New Yorker called it "virtuosic."[18] Marxist literary critic Fredric Jameson found its new, science fiction-inflected variation on the historical novel now "defined by its relation to future fully as much as to past."[19] Richard Murphy said in the Review of Contemporary Fiction that Mitchell had taken core values from his previous novels and built upon them.[20]

Criticism focused on the book's failure to meet its lofty goals. F&SF reviewer Robert K. J. Killheffer praised Mitchell's "talent and inventiveness and willingness to adopt any mode or voice that furthers his ends," but noted that "for all its pleasures, Cloud Atlas falls short of revolutionary."[21] Theo Tait of The Daily Telegraph gave the novel a mixed review, focusing on its clashing themes, saying "it spends half its time wanting to be The Simpsons and the other half the Bible."[22]

In 2019, Cloud Atlas was ranked 9th on The Guardian's list of the 100 best books of the 21st century.[23]

In 2020, Bill Gates recommended it as part of his Summer Reading List.[24]

Awards and nominations

[edit]The book won the Literary Fiction Award at the 2005 British Book Awards and the Richard & Judy Book of the Year Award.[25] It was shortlisted for the Booker Prize.[26] It was nominated for the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 2004,[27] and the Arthur C. Clarke Award in 2005.[28]

Structure and style

[edit]The book has been described as incorporating elements of metafiction,[29] historical fiction, contemporary fiction and science fiction into its narrative.[30][31] The book's style was inspired by Italo Calvino's If on a winter's night a traveler, which contains several incomplete, interrupted narratives. Mitchell's innovation was to add a 'mirror' in the centre of his book so that each story could be brought to a conclusion.[32][3]

Mitchell has said of the book:

Literally all of the main characters, except one, are reincarnations of the same soul in different bodies throughout the novel identified by a birthmark ... that's just a symbol really of the universality of human nature. The title itself Cloud Atlas, the cloud refers to the ever changing manifestations of the Atlas, which is the fixed human nature which is always thus and ever shall be. So the book's theme is predacity, the way individuals prey on individuals, groups on groups, nations on nations, tribes on tribes. So I just take this theme and in a sense reincarnate that theme in another context ...[33]

Textual variations

[edit]Academic Martin Paul Eve noticed significant differences in the American and British editions of the book while writing a paper on the book. He noted "an astonishing degree" of variance and that "one of the chapters was almost entirely rewritten".[34] According to Mitchell, who authorized both editions, the differences emerged because the editor assigned to the book at its US publisher left their job, leaving the US version un-edited for a considerable period. Meanwhile, Mitchell and his editor and copy editor in the UK continued to make changes to the manuscript. However, those changes were not passed on to the US publisher, and similarly, when a new editor was assigned to the book at the US publisher and made his own changes, Mitchell did not ask for those to be applied to the British edition, which was very close to being sent to press. Mitchell said: "Due to my inexperience at that stage in my three-book 'career', it hadn't occurred to me that having two versions of the same novel appearing on either side of the Atlantic raises thorny questions over which is definitive, so I didn't go to the trouble of making sure that the American changes were applied to the British version (which was entering production by that point probably) and vice versa."[35]

Film adaptation

[edit]The novel was adapted to film by directors Tom Tykwer and the Wachowskis. With an ensemble cast to cover the multiple storylines, production began in September 2011 at Studio Babelsberg in Germany. The film was released in North America on 26 October 2012. In October 2012, Mitchell wrote an article in The Wall Street Journal called "Translating 'Cloud Atlas' Into the Language of Film" in which he compared the adapters' work to translating a work into another language.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ Begley, Interviewed by Adam (2010). "Paris Review - The Art of Fiction No. 204, David Mitchell". The Paris Review. Vol. Summer 2010, no. 193.

- ^ Staff Writer. "Against all odds, David Mitchell's novel 'Cloud Atlas' now a film". Akron Beacon Journal. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ a b Turrentine, Jeff (22 August 2004). "Washington Post". Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ Mitchell, David (5 February 2005). "The book of revelations". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas". Critics & Writers. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Books of the moment: What the papers say". The Daily Telegraph. 6 March 2004. p. 190. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas". Book Marks. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell". The BookScore. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas By David Mitchell". Bookmarks. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas". Complete Review. 4 October 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ Oakes, Keily (17 October 2004). "Review: Cloud Atlas". BBC. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas Review". Kirkus Reviews. 15 May 2004. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Miller, Laura (14 September 2004). "Cloud Atlas Review". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Anderson, Hephzibah (28 February 2004). "Observer Review: Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell". The Observer. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Byatt, A. S. (28 February 2004). "Review: Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Turrentine, Jeff (22 August 2004). "Fantastic Voyage". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas". The New Yorker. 23 August 2004. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Fredric Jameson, The Antinomies of Realism, London and New York: Verso, 2013, p. 305.

- ^ Murphy, Richard (2004). "David Mitchell. Cloud Atlas". The Review of Contemporary Fiction.

- ^ "Books", F&SF, April 2005, pp.35-37

- ^ Tait, Theo (1 March 2004). "From Victorian travelogue to airport thriller". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ "The 100 best books of the 21st century". The Guardian. 21 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Gates, Bill (18 May 2020). "5 summer books and other things to do at home". Gates Notes. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ post, The Conservatism of Cloud Atlas was published on You can annotate or comment upon this (21 June 2015). "The Conservatism of Cloud Atlas". Martin Paul Eve. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ "David Mitchell | The Booker Prizes". thebookerprizes.com. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Fictions, © 2023 Science; SFWA®, Fantasy Writers Association; Fiction, Nebula Awards® are registered trademarks of Science; America, Fantasy Writers of; SFWA, Inc Opinions expressed on this web site are not necessarily those of. "Cloud Atlas". The Nebula Awards®. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Arthur C. Clarke Award". The Arthur C. Clarke Award. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Brown, Kevin (2 January 2016). "Finding Stories to Tell: Metafiction and Narrative in David Mitchell's Cloud Atlas". Journal of Language, Literature and Culture. 63 (1): 77–90. doi:10.1080/20512856.2016.1152078. ISSN 2051-2856. S2CID 163407425.

- ^ Hicks, Heather J. (2016), Hicks, Heather J. (ed.), ""This Time Round": David Mitchell's Cloud Atlas and the Apocalyptic Problem of Historicism", The Post-Apocalyptic Novel in the Twenty-First Century: Modernity beyond Salvage, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 55–76, doi:10.1057/9781137545848_3, ISBN 978-1-137-54584-8, S2CID 144729757, retrieved 5 December 2023

- ^ De Cristofaro, Diletta (15 March 2018). ""Time, no arrow, no boomerang, but a concertina": Cloud Atlas and the anti-apocalyptic critical temporalities of the contemporary post-apocalyptic novel". Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 59 (2): 243–257. doi:10.1080/00111619.2017.1369386. ISSN 0011-1619. S2CID 165870410.

- ^ Mullan, John (12 June 2010). "Guardian book club: Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ^ "Bookclub". BBC Radio 4. June 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ Eve, Martin Paul (10 August 2016). ""You have to keep track of your changes": The Version Variants and Publishing History of David Mitchell's Cloud Atlas". Open Library of Humanities. 2 (2): 1. doi:10.16995/olh.82. ISSN 2056-6700.

- ^ Alison Flood (10 August 2016). "Cloud Atlas 'astonishingly different' in US and UK editions, study finds". The Guardian.

- ^ Mitchell, David (19 October 2012). "Translating 'Cloud Atlas' Into the Language of Film". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Dillon, S. ed. (2011) David Mitchell: Critical Essays (Kent: Gylphi)

- Eve, Martin Paul. "Close Reading with Computers: Genre Signals, Parts of Speech, and David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas." SubStance 46, no. 3 (2017): 76–104.

External links

[edit]- David Mitchell discusses Cloud Atlas on the BBC's The Culture Show

- Cloud Atlas at complete review (summary of reviews)

- Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell Archived 4 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, review by Ted Gioia (Conceptual Fiction)

- 2004 British novels

- British Book Award–winning works

- 2004 science fiction novels

- 2004 fantasy novels

- Fiction set in 1850

- Fiction set in 1931

- Fiction set in 1975

- Novels set in the 1850s

- Novels set in the 1930s

- Novels set in the 1970s

- Novels set in the 22nd century

- Novels set in the 24th century

- British science fiction novels

- British fantasy novels

- British novels adapted into films

- Novels about cannibalism

- Novels about cloning

- Dystopian novels

- Epistolary novels

- Frame stories

- British post-apocalyptic novels

- Books written in fictional dialects

- Male bisexuality in fiction

- Novels by David Mitchell

- Metafictional novels

- Novels set in Belgium

- Novels set in Bruges

- Novels set in California

- Novels set in England

- Novels set in Korea

- Novels set in Hawaii

- Novels set on islands

- Novels about reincarnation

- Sceptre (imprint) books

- Novels set in New Zealand

- Chatham Islands

- Science fantasy novels

- Science fiction novels adapted into films

- Nonlinear narrative novels

- Novels about bisexual topics

- LGBTQ speculative fiction novels

- Novels set in the 21st century

- Novels set in the 19th century

- Novels set in the 20th century

- 2004 LGBTQ-related literary works